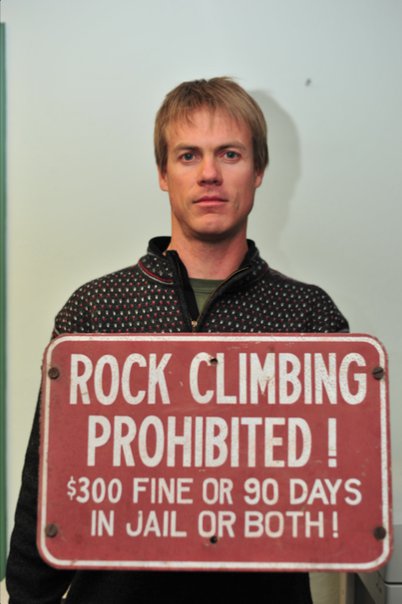

// Local Limelight: Brady Robinson

Brady Robinson has been Executive Director of the Access Fund for ten years now. Along his journey, he has narrowly escaped an avalanche, dabbled in aviation, festered on a two-person portaledge with three grown men, and lived a dirtbag’s dream in Yosemite Valley.

Today, Brady is a full-time family man, outdoor enthusiast, and conservationist. Talking with him is an authentic and refreshing experience; he’s professional but maintains the grit of a climber and is informed without being patronizing.

Read on:

So, Brady, tell me about your history as a climber—especially the days of you eating pizza out of a trashcan.

(Laughs) I was an aspirational dirtbag. Back in those days, at least in Yosemite Valley, taking on an aura of homelessness was sort of a sign of legitimacy. I taught myself how to climb out of a book I bought in Minnesota. I survived that experience, luckily.

In college, I worked at a boy’s camp in the Poconos of Pennsylvania and was mentored by a real climber. That’s kind of where I learned a higher level of the craft. Eventually, I learned to ice climb and became an alpine climber.

My climbing history has been a combination of audaciously doing things I was not qualified to do, avoiding injury and then finding mentors along the way to help out.

Who was your main mentor?

Roland Rincon. He’s a geologist. He was mentoring me back in the day when 5.11 trad was still considered pretty freaking hard. He was willing to deal with me for whatever reason—very patiently.

Who was your primary climbing-partner in crime?

Jimmy Chin. I don’t know what my climbing career would have looked like without him. He’s my brother from another mother. When we started climbing together, I had a little more experience than he did, and we had a very good partnership.

We were well suited in climbing ability, risk tolerance, and goals. I was always better at hauling loads on the wall than he was—because I weighed more! But that was the only thing I was consistently better at. Finding someone you are well matched with on so many levels is a rare, wonderful thing.

Hear, hear. Where else did your adventures with Jimmy take you?

We went on three trips to Pakistan, and one trip to Patagonia. While we were training for one of our trips to Pakistan, I had brought an old Nikon FE manual film camera. I was teaching him the basics of shutter-speed and F-stops, and he took two or three shots on an El Cap climb. When I submitted all the photos to Mountain Hardwear, they picked one of his pictures. It was 1999, and that was the first photo he ever sold. A few years ago I gave him that camera and lens and said ‘this is the one that launched it.’

Now, I’m about to turn 45, and I think at this stage of life, there’s nothing like the friends you’ve shared transformative experiences with for decades. There’s a classic photo of Jimmy I’ll find for you; I’m wearing super short-shorts.

That’s always a good look! You mentioned that you became an alpine climber, but I understand you no longer embark on expeditions. What was that transformation like?

It was when I was in the Waddington Range with Jimmy, Conrad Anker and Peter Croft in 2002 that I realized I was surrounded by people who were professional climbers, and there was a big part of me that wanted that, but it just didn’t feel like my path.

When you’re on these trips with superstars, and you’re not a superstar, there are some moments of doubt as you try to find your identity and reflect on your life’s direction.

I don’t want to sound like I’m making excuses—it’s not that—it’s just, there are moments in anyone’s career where you wonder ‘am I going this way or that way?’

I had met the woman who would be my wife, I had an amazing career with Outward Bound at the time, and I didn’t want to be an expedition climber anymore. That was one of my last major trips.

We all find our paths. I am very happy with mine.

Where did your path take you after that?

My wife’s dad was sick, so we moved to the southeast to be near her family. I got a desk job which further extended my identity crisis, and to cope with that, I learned to fly airplanes.

Casual.

I was freaking out—it was my first desk job. I felt like I was settling and I still wanted adventure. It turns out, when you’re not a very good pilot, you can scare the sh*t out of yourself in a small aircraft really quickly.

I’m going to keep that in mind, for the next time I feel like I’m bored. What was the desk job?

I was the Operations Director of North Carolina Outward Bound. It was like non-profit management boot camp—an experiential MBA of sorts. I was in charge of all program safety, quality and efficiency. It taught me so much, and it’s why I was somewhat qualified for the job at Access Fund, which I started in 2007.

It’s been ten years since you became the Executive Director of Access Fund. What’s been the hardest part of your job?

One of the challenges in a non-profit is the concept of soft power.

What’s that?

We have to find a leverage point to make a difference in the world; we can’t just come out and tell people what to do because ultimately we don’t have any authority to do that. We have to weave ourselves through something, find some other kind of authority. Soft power is the medium that the Access Fund is working in most of the time.

We also deal with the fact that we’re an organization from Boulder, Colorado, and for many people, that’s a negative connotation. So when we are dealing with local climbing organizations around the country, how do we support them and ultimately advance our mission of keeping climbing areas open and conserved? Increasingly, the answer has been to hire regional staff and support grassroots, local efforts.

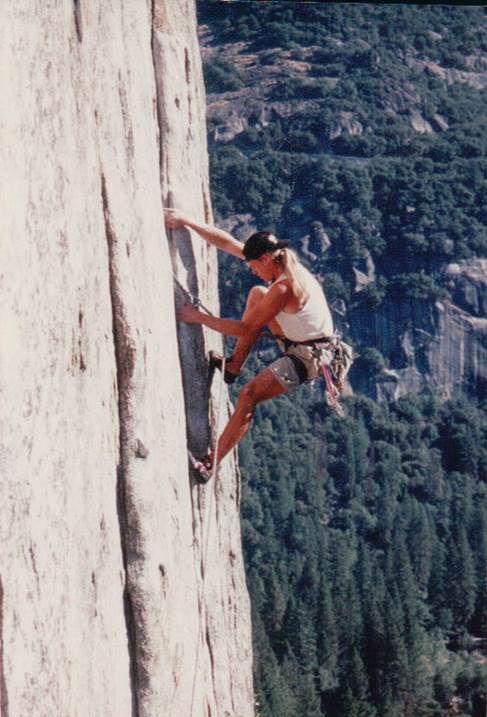

Steph Davis, David Anderson and Jimmy Chin do a summit dance after making the first ascent of Tahir Tower, Kondus Valley, Pakistan. (2000)

What obstacles have you (and the Access Fund) overcome in the past decade?

At the beginning, back in the 90s, it felt like we were David in a David and Goliath battle. In those sorts of battles, slinging rocks at people is one of your only strategies. I don’t think we’re in that battle anymore. Climbers have a voice; people care what we say. We get a lot more done when we work with other people, organizations, and agencies. One of the things I’m most proud of on the political side is our work with the Inter-Tribal Coalition on the Bears Ears National Monument.

One product of this work is a beautiful letter that outlines the meetings we had between the climbers and the tribes. In the letter, the tribes say that climbing should continue to occur in Bears Ears, and furthermore, climbing should be explicitly mentioned in the Presidential proclamation that designates the monument. That’s huge. We spent years building trust over time. It got to the point that we agreed the best thing to do would be to independently write letters to the Secretary of the Interior, Sally Jewell.

That is the first time ever, in a presidential proclamation, that climbing or recreation, in general, has been mentioned. Obama signed a piece of paper that had ‘climbing’ on it. We could talk for a whole hour on the various partners, agencies, and work that went into making that happen. Just those two words: ‘rock climbing’ took over a year of advocacy.

Jeebus. That is amazing progress. In your TED Talk (2013) you said ‘human-powered recreation can help secure the future of the conservation movement.’ What are four things we can do today to get involved?

- If you’re intrigued by Bears Ears, go check it out. Hike, bike or even rent a Jeep and ride into the middle of nowhere, just stay on designated roads please. Get out there and get dirty and experience these places, in whatever way that makes the most sense to you.

- Pay attention and read news from sources you trust. When we pay attention, we are part of a ground swell that can exact a political price that affects decisions. The public process doesn’t always work the way we expect, but the administrators are listening.

- Post on social media. Some people might call this political slacktivism, but it’s something. It all adds up. I don’t buy into the ‘everyone has to be a political expert to weigh in.’ For some of us, it’s our life, and for some of us, it’s 10 minutes. Do what you can.

- Figure out the local climbing organization where you are and get on their mailing list. Throw them and the Access Fund a few bucks. If each climber volunteered one day a year, oh my god, that would be a tangible change.

We’re aiming to raise $5,000 for the Access Fund this month. For all of October’s activities, visit this page.